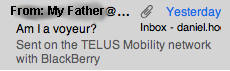

Due to the time difference between Canada and Australia, when my family sends me e-mails throughout their day, I get them in one big stack first thing in the morning. These e-mails usually contain irreverent updates about life in Canada meant to make me homesick so that I return to them after I finish my PhD. It works rather well. One day I found the following e-mail sitting in my Inbox:

Now, maybe that subject line would be cause for concern if my dad was not my dad. But my dad is the kindest, sweetest, gentlest person I know, and there was no chance anything unpleasant lay within the body of that e-mail. Actually, it turned out to be pretty cool. This is what my dad found:

Worms! Doing IT!

That's two earthworms lined up anti-parallel. It gave me flashbacks to first year undergrad biology. There, while preparing to dissect earthworms, we learned all about their reproduction. The wide, smooth band on each worm is the clitellum, which contains both male and female reproductive organs. Each worm lines up its clitellum with the sperm receptacle of the other worm, which is located between the worm's clitellum and its mouth. Then, each worm passes a packet of sperm from its clitellum to the other worm's sperm receptacle. It turns out my dad got a picture of that as well:

The two white globs inbetween the worms are sperm packets.

After the sperm packets are exchanged, the worms separate and each secretes an egg packet from its clitellum. The worm slides the egg packet along its body until the egg packet reaches the sperm receptacle, and then the whole mess of eggs and sperm (and rather a lot of mucus) slides off the worm. If you want more details, you can find them here, rather uncomfortably explained in the first person.

I have never seen this in my entire life. In one morning, my dad came across not one pair of worms, but five! Those two pictures above are of two different pairs of worm-lovers! Here's another:

Was there something in the air that day? In the soil? Also, my dad probably could have found more worm-lovers. He quit looking because he "was starting to feel a little awkward."

AWKWARD...

Notice how each worm's butt is still in a hole? These worms aren't crawling around like after rain. The fifth pair of worms were shyer and shot back into their respective burrows ("like rubber bands") before my dad could get a picture. Worms only half emerge from their burrows to mate! They keep their lower-halves indoors to make for a rapid escape if necessary.

My dad clitellum-blocked them.